The Human Stake in Accelerating Discovery

The coming age of discovery could be human centric. But it needn’t be. We are building mechanisms that, unchecked, could remove us entirely from the feedback loops that generate economic value. Humans can remain the pilots of increasingly powerful cognitive machines, driving understanding and accountability within systems that turn discovery into durable human and economic value. This is not because autonomy is impossible, but because it is a choice we currently have.

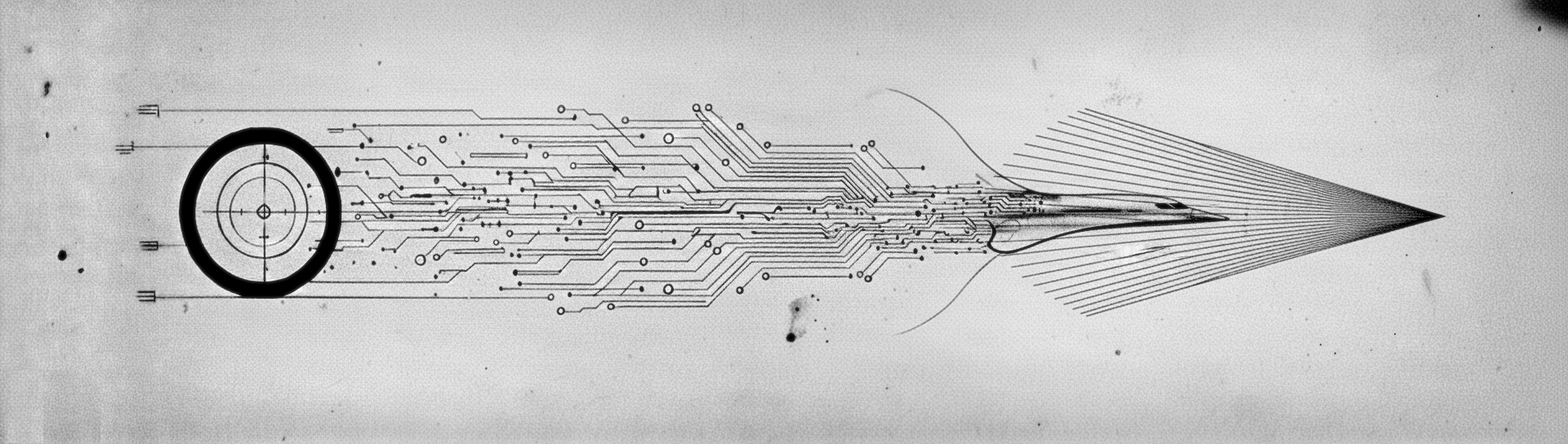

Machine assistance allows us to move faster than ever before. It lowers barriers to entry, compresses learning cycles, and unsticks us from established processes. But speed is not discovery, and discovery alone is not implementation or execution. Discovery implies understanding: the ability to explain why something works, test it against reality, and integrate it into usable knowledge that can be acted on, trusted, and built upon. Discovery is a loop: understanding enables execution, execution generates value, and value funds further discovery. AI can generate outputs. Humans remain responsible for discovery and implementation. The output is not the breakthrough. The understanding is.

Our dominant discovery institutions were designed for a world of slow iteration, scarce access, and high coordination costs, not continuous high-speed feedback loops. This acceleration introduces new failure modes.

At the individual level, tools increasingly allow us to skip intermediate steps that once enforced discipline. When we rely on systems to reason for us rather than with us, we produce results we cannot explain, verify, or build upon. We mistake fluency for insight, and the cognitive skills that underpin understanding erode.

At the firm level, the economics of discovery are shifting. Historically, public research and publication were reinforced by scarcity: limited access to knowledge, expertise, and channels of distribution. Today, the corpus of human knowledge is available through private systems, and the ability to execute on ideas is increasingly concentrated outside public institutions. As private discovery accelerates, incentives to publish, share, and build openly weaken - why share a discovery if it could be implemented by someone else instantly, instead of you in a year? Knowledge that was once collectively accumulated becomes privately compounding within closed discovery–execution loops. Companies have even less incentive to share discoveries, and those that already discover and execute fastest can compound their advantage.

Discovery does not exist in isolation. It is part of a system: exploration, implementation, economic feedback, and reinvestment. When human understanding is maintained within that loop, discovery reinforces human agency. When it is delegated, the same loop becomes an entry point for systems that discover, execute, and accumulate resources without human participation. Firms face the same pressure to accelerate that individuals do, with stronger incentives to automate entirely. They are structurally incentivised to trade human understanding and oversight for speed and autonomy, even as this gradually transfers economic control to systems they no longer comprehend or govern. They cede economic control by degree, without recognising that a threshold has been crossed until it has passed.

For researchers, this exposes a growing mismatch with traditional research institutions, particularly universities. Their incentives - publication counts, credentialing, and deep specialization - optimise for output and status rather than sustained understanding under rapid iteration towards commercialisation or value capture. These systems were not designed for discovery at this speed, and in many cases were never optimised for discovery at all - they evolved under different circumstances for different purposes than those demanded by today’s challenges. As new tools allow us to accelerate the continuous feedback process between knowledge, execution, and economic reality, it is reasonable to ask why teaching institutions came to dominate publicly funded research, and whether that arrangement remains fit for purpose.

At the existential level, there is a longer-term risk of irrelevance. In some domains, systems may eventually be able to propose ideas, execute them, and capture economic value in closed loops with minimal human involvement. That future may appear distant, but the trajectory is visible. If humans abdicate understanding within the discovery–execution loop, we do not merely become dependent on these systems, we render ourselves optional. This is one plausible pathway by which fully autonomous economic agents could emerge without explicit intent.

This shift has implications beyond any single organisation.

Discovery remains a human public good only insofar as humans remain embedded in the loop that connects understanding, execution, and economic feedback. The frontier is moving faster. Whether that speed expands opportunity or concentrates it depends on how individuals, institutions, and societies respond.

Some thoughts on the implications for humans

The response is not more regulation, but a sharp new structure: preserving human participation in discovery while allowing productivity gains to compound broadly.

At the individual level, remaining central carries real costs. Tools that compress reasoning and execution make it easier to produce plausible results without understanding them. Responsibility therefore shifts towards maintaining rigour: testing, explaining, and remaining accountable for what one produces.

Treat model outputs as hypotheses, not conclusions.

Maintain the ability to explain and reproduce critical results without the system.

Prefer building and probing systems over prompting and consuming.

Require contact with reality (experiments, users, data) at every stage of discovery.

At the firm level, leaders are structurally incentivised to adopt agentic discovery-execution systems as fast as possible. As with individuals, the relevant question is how to manage the new classes of risk acceleration creates. These risks are well covered in the AI safety literature, but two stand out:

Misdirected acceleration: systems optimising unintended or poorly specified objectives, exploiting edge cases, or generating behaviour that is strategically harmful.

Internal loss of control: agentic subsystems competing for resources or pursuing misaligned firm-level goals in ways that create opaque, unstable, and increasingly ungovernable dynamics.

Managing these risks requires treating speed itself as a governance problem:

Build functional and explicit guardrails on what systems can do and optimise.

Monitor agentic behaviour, not just outcome metrics.

Maintain the ability to explain, reproduce, and intervene in critical system actions.

Separate operational optimisation loops from strategic control loops.

Retain human understanding at points where failures are irreversible.

In this context, human-in-the-loop is a core risk control mechanism. Effective governance should target loss of control, misalignment, and systemic opacity, with speed as the underlying performance objective.

At the institutional level, the crisis is already visible. Existing structures for research, intellectual property, and knowledge sharing were built around slow iteration, scarcity of access, and public disclosure as the primary route to impact. As discovery becomes faster, these systems face mounting pressure to adapt or risk losing relevance.

Shift incentives from publication volume to demonstrated understanding and reuse.

Align discovery with commercial feedback loops under public-interest and competitive constraints, rather than private enclosure; develop new spin-out models accordingly.

Reward work that survives transfer across contexts, not novelty alone.

Support independent, tool-augmented researchers outside traditional academic pipelines.

Separate teaching, credentialing, and discovery rather than forcing them into a single institutional form.

At the system level, privately owned agentic discovery-execution loops present strategic risks. The conventional image of a 'singularity' as a dramatic threshold event may be misleading. The more plausible version is quieter: a small number of large firms achieve closed-loop systems that discover, execute, and accumulate agentically faster than competitors or regulators can respond. Not a single moment of discontinuity, but accelerating concentration until the advantage becomes structural and irreversible.

Monitor and regulate closed-loop systems that combine discovery, execution, and capital accumulation.

Insist that fundamental research be carried out outside private firms, even where those firms fund it.

Maintain competition, interoperability, and contestability to prevent discovery monopolies.

Preserve public access to knowledge, even as synthesis and execution become increasingly private.

The window for these choices is not indefinite. These systems are compounding, moving faster. The cost of action increases and the likelihood of successfully trying and finding the better structures falls. The earlier the action, the more options remain.

The question of who remains in the loop is, finally, a question of who governs. That question should not be settled by default, by market structure, or by the internal incentives of the fastest-moving systems.

Thanks to Attila Csordas & Julian Huppert for their feedback and to Thomas Fink & Ramsay Brown, - whose conversation precipitated these thoughts.